Art & Culture

Oedipus & Hamlet

Fate and Free Will.

By: Michael Vitaro 🇨🇦

2024-11-17

Oedipus & Hamlet — Fate and Free Will

Are we masters of our own destiny or do unseen forces weave the threads of our lives? This tension between fate and free will drives two of literature's greatest tragedies, Oedipus Rex and Hamlet. Both plays raise fundamental questions about humanity. To what degree are the protagonists in control of their own fates? Which of them truly exercises free will? Comparing these two iconic figures reveals how cultural frameworks shape human understanding of destiny and agency.

In Ancient Greece, beneath the open sky and the gods’ watchful gaze, a theatre hums with anticipation. In this sacred space, a tragedy unfolds. The audience shares an understanding that the cosmos are bound by the will of those watching eyes—their role to simply play it out. They believed in fatalism, where destiny is preordained. As Oedipus Rex begins, Apollo’s will unravels. Through prophecy, King Oedipus learns he must unravel a murder and end the plague on Thebes. It’s this same prophecy that sets him on a path doomed from inception. His quest for justice and his determination only draw Oedipus closer to the catastrophe he so desperately tries to avoid.

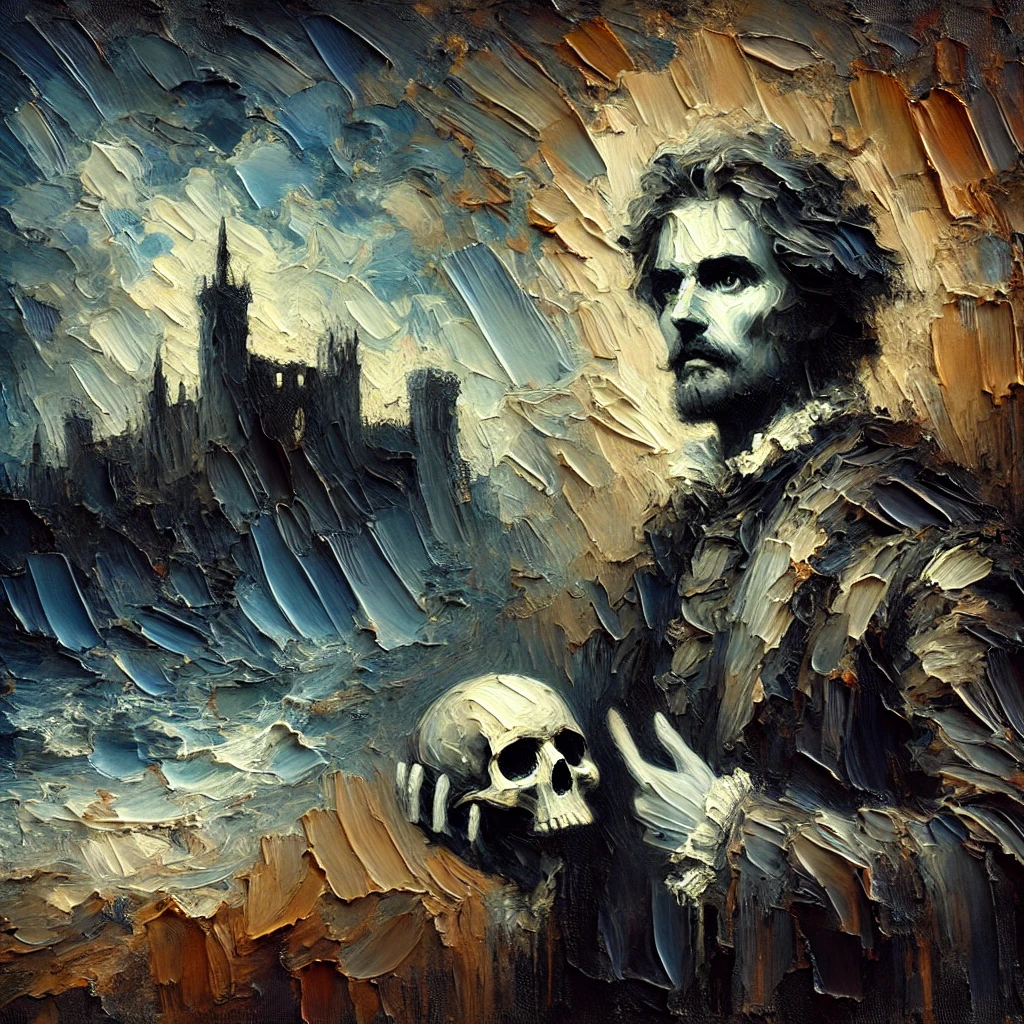

In Renaissance London, along the Bankside of the River Thames, a playhouse buzzes with energy. Nobles comfortably sheltered high above encircle the peasants shuffling in the open-air pit. Like the theatre, Hamlet reflects the Elizabethan worldview. At its core lay the Great Chain of Being, a hierarchy ordaining all things from sovereign to stone. This chain was balanced through divine providence. To spoil it meant inviting darkness, chaos, and disease. The words 'Something is rotten in the house of Denmark' signal that disorder has taken root. When Hamlet is told 'Murder most foul,' the audience knows what he must do: avenge his father’s death and restore balance to the kingdom. Yet, throughout the play, Hamlet hesitates. His tragedy stems from his intellectual paralysis and inability to reconcile his duty with the existential weight of his choices.

Both Oedipus and Hamlet are bound by intimate knowledge and guided by external hands. Separated by 2,000 years, their stories offer deep insight into how humanity governs itself and the forces governing it. To understand what they say about agency, we must interrogate how each play confronts these ideas and how their protagonists navigate the tension between free will and fate.

Contrasting Worldviews: Ancient Greeks vs. Elizabethans

'Man’s wisdom is nothing; the gods know all.'

This declaration by the Chorus encapsulates the essence of Oedipus Rex: mortals, no matter their achievements or wisdom, are powerless before divine will. At the play’s start, Oedipus is exalted as a saviour who delivered Thebes from the Sphinx. Yet, as the tragedy unfolds, the Chorus reflects his fall from a revered leader to a blind beggar, stripped of all status.

Even as an infant, his mother Jocasta tries to defy the gods by abandoning Oedipus to die. Yet this act of defiance only binds Oedipus more tightly to fate. As the play closes, the Chorus offers its final sigh: 'Count no man happy till he dies, free of pain at last.' A reminder that even the greatest among us must suffer through forces beyond our control. His story is not one of choice but of inevitability.

By contrast, Elizabethans embraced a more dynamic view of existence. Shakespeare investigates agency with greater nuance. 'To thine own self be true' appears as practical advice but carries sharp irony. Delivered immediately after Polonius’s prescriptive advice to his son Laertes and before he strips his daughter Ophelia of her agency, the line mocks the very idea of self-determination. Polonius—the eternal meddler—embodies a world where agency is shaped by societal and familial expectations. The irony underscores Shakespeare’s exploration of free will within the constraints of providence, where human autonomy is both empowering and limited.

'There’s a divinity that shapes our ends, rough-hew them how we will.'

Hamlet acknowledges the dynamic balance between divine influence and human choice. Renaissance England, emerging from the chaos of the Hundred Years’ War and the plague, viewed divine order as essential to countering human turmoil. In Hamlet, Shakespeare explores this interplay through his protagonist’s moral and existential struggles, revealing how personal decisions unfold among forces striving to restore balance.

'Alexander died, Alexander was buried, Alexander returneth to dust; the dust is earth.'

In this reflection, Hamlet contemplates death as the ultimate equalizer, a reminder that all human effort—whether noble or corrupt—ends in dust. This meditation deepens Hamlet’s comment on agency. Death, as an unavoidable force, limits human autonomy yet also clarifies the stakes. In the face of mortality, the struggle for agency becomes both poignant and profoundly constrained. This dichotomy between Greek fatalism and Elizabethan providence sets the stage for a deeper exploration of how these frameworks shape their protagonists' destinies.

Agency in Action: Oedipus vs. Hamlet

'O light, let me look at you one final time, a man who stands revealed as cursed by birth, cursed by my own family, and cursed by a murder where I should not kill.'

These words capture Oedipus’s tragic realization and duality—striving for control yet powerless against fate. Blinded by overconfidence, he ignores every warning in his relentless pursuit of truth, fulfilling the prophecy he seeks to escape. 'You are the murderer you seek.' Oedipus accuses the seer of treachery and conspiring with his half-brother Creon. His pursuit culminates in the revelation of his identity and his literal blinding—a symbolic act of self-punishment and an acknowledgment of his fate. As he laments, 'It was Apollo, friends, it was Apollo. He brought on these troubles…But the hand which stabbed out my eyes was mine alone.' Oedipus accepts his role in enacting his destiny while recognizing the inevitability of divine will.

While Oedipus operates under fatalism, Hamlet is bound by providence. His fate hinges on his efforts to restore divine balance. 'What a piece of work is a man! How noble in reason, how infinite in faculty, in form and moving how express and admirable; in action how like an angel, in apprehension how like a god!' Here, Hamlet marvels at human potential, reflecting the Renaissance celebration of reason, individuality, and providence. Yet this idea is undercut by Hamlet’s indecision, unable to reconcile his awe for human capacity with the consequences of inaction.

'Now might I do it pat, now he is praying; / And now I’ll do’t. And so he goes to heaven.'

Hamlet is wrestling with an Elizabethan concern: the afterlife. He fears granting Claudius salvation while he repents. Here, Hamlet contemplates the moral and metaphysical consequences of his choices, delaying his actions.

'To be, or not to be: that is the question.'

This famous soliloquy embodies his internal conflict. As he weighs the nobility of enduring suffering against the uncertainty of action, he reflects the tension between humanity and the divine. This moment of profound introspection highlights Hamlet’s intellectual engagement with the concept of agency.

Fate and Choice: Sophocles vs. Shakespeare

Both Oedipus Rex and Hamlet are timeless tragedies that explore the question of human agency, yet they diverge sharply in their treatment of fate and choice. In Oedipus Rex, every character serves to highlight Sophocles’s view of fate’s unyielding power. Jocasta’s attempt to thwart the prophecy and Creon’s role in the unraveling of Oedipus’s life underscore the futility of human resistance to divine will.

In Hamlet, the protagonist’s internal conflict remains the focus, while supporting characters add nuance to the discussion. Laertes and Fortinbras’s decisiveness contrasts Hamlet’s hesitation. Ophelia and Gertrude’s limited autonomy reflects societal constraints on women. Polonius and Claudius’s manipulative ambition underscores the play’s concern with action, consequence, and the corruption of power. These complexities expand the thematic scope of Hamlet.

In a modern philosophical context, these plays invite us to question the very nature of free will. Is it the ability to act independently, or the capacity to make meaningful choices within the constraints of our lives? While Oedipus is locked in the inexorable grip of fate, Hamlet’s existential questioning reveals a more complex negotiation between divine order and human autonomy. Through these tragedies, Sophocles and Shakespeare reflect our enduring quest to understand ourselves and the forces that guide us.